Buddy, Gus, Nike, Prince, Shadow, Dolly and Sunshine.

These are the names of a very important health care team that works diligently to improve patient outcomes — through tail wags and cuddles.

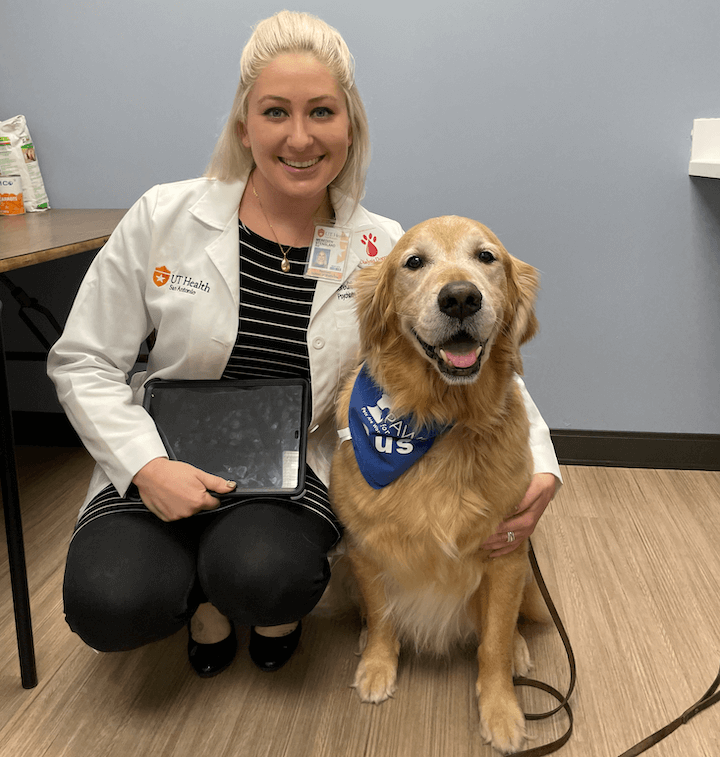

The Dialysis Doggos, as they’re lovingly referred, are part of a research study being conducted by Meredith L. Stensland, PhD, LMSW, assistant professor of research in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences.

The study investigates the effect of an animal assisted intervention for patients receiving dialysis, and if this intervention improves symptoms of pain and depression and reduces the number of skipped dialysis treatment sessions.

“This is the first time an intervention like this has been done for dialysis patients,” Dr. Stensland said. “It’s a safe, non-addictive, non-pharmacological approach to treating chronic pain and depression, both of which are prevalent among dialysis patients.”

Dr. Stensland’s interest in researching pain and animal assisted interventions was sparked after her experience working as hospice social worker providing end-of-life care.

“During this time, I observed the comfort that therapy dogs provided to terminally ill patients in pain,” Dr. Stensland said. “I know that this is beneficial to patients. But I want to help produce empirical evidence and add to the base of knowledge when it comes to animal interventions. It can be helpful to patients in ways that other interventions just can’t.”

Dr. Stensland explained that unmanaged chronic pain and depression are known predictors for patients missing dialysis treatment sessions, which can quickly lead to hospitalization and very poor outcomes for patients. Given the nature of dialysis treatment, which requires patients to attend four-hour sessions three times a week, finding ways to make the experience more comfortable and enjoyable can have great benefits.

She also explained that past research of animal therapy has shown that interacting with a dog can have a significant impact on specific biomarkers related to pain and stress. The act of petting a dog releases oxytocin and lowers cortisol levels, which play a role in both pain processing and mood.

In addition, the dogs can act as an extended social support network for patients, which is known to be linked to improved health outcomes for patients of all kinds.

“The patients form a bond with the dog and look forward to seeing them. They even ask for more visits, which is difficult for us because if the patient was randomized to one visit a week, we must stick to that even when they are requesting more visits. We’ve had a lot of positive feedback,” Dr. Stensland said.

Patients participating in the study enroll for 12 weeks. During the first two weeks, the patient does not receive any therapy dog visits to form the baseline. In the remaining weeks, a pre-test/post-test design is used to assess the therapy dog intervention. Patients take a pre-test assessing their pain level and mood in the waiting room. Then they get to interact with the therapy dogs. After plenty of play, pets and cuddles, the dog is removed from the room and the patient takes another assessment of their pain and mood. All of these steps occur prior to the patient going back to the treatment floor for dialysis.

Patients participating in the study enroll for 12 weeks. During the first two weeks, the patient does not receive any therapy dog visits to form the baseline. In the remaining weeks, a pre-test/post-test design is used to assess the therapy dog intervention. Patients take a pre-test assessing their pain level and mood in the waiting room. Then they get to interact with the therapy dogs. After plenty of play, pets and cuddles, the dog is removed from the room and the patient takes another assessment of their pain and mood. All of these steps occur prior to the patient going back to the treatment floor for dialysis.

“The hope is they get a little oxytocin boost, lower their cortisol, and perhaps have the experience of receiving dialysis be less stressful and less uncomfortable.” Therapy dogs represent a unique approach to treatment adherence through improved symptom management.

The therapy dogs and their handlers are provided by volunteers from several organizations including the local chapter of Pet Partners, Therapy Animals of San Antonio and Pets Are a Wonderful Support (PAWS). Partners from Paws Up Pet Therapy Program out of the University Health System played a key role in setting up contacts for the study, Dr. Stensland said.

Although results from the data collection aren’t back yet, Dr. Stensland can see many possibilities for the benefits of animal assisted interventions. She is currently in the process of organizing therapy dog sessions for affiliated UT Health San Antonio outpatient site clinics New Opportunities for Wellness and the Transitional Care Clinic.

“Going to the doctor or receiving treatment can be a nerve-wracking process,” she said. “To sit in the waiting room and have someone looking up at you with unconditional acceptance, that can go a long way with patients.”